Works of Amir Hossein Safdarzadeh Haghighi

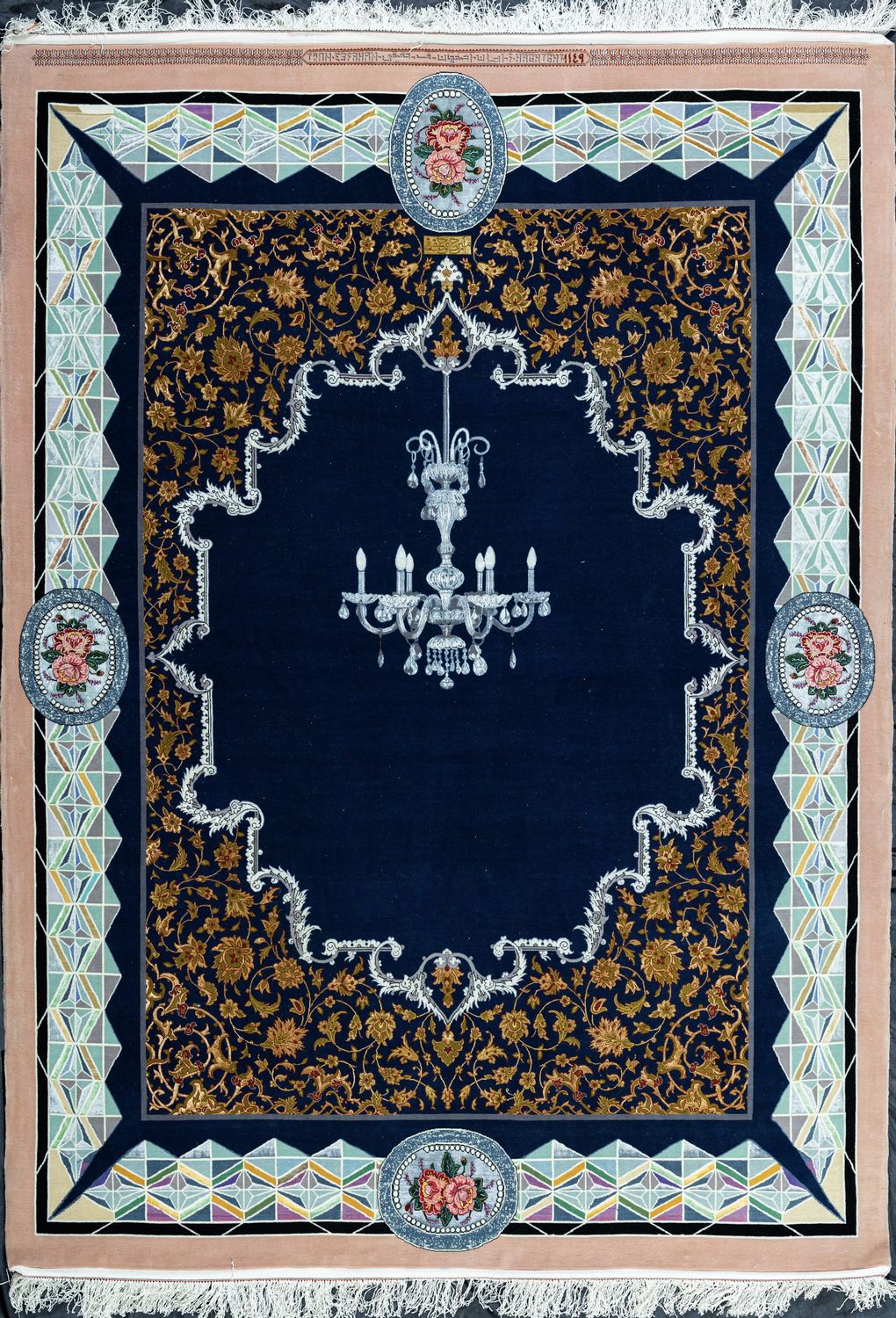

Carpet of Light (Nour)

Description

Designed in 2018 by Amirhossein Haghighi, Carpet of Light (Nour) was woven by Anis Karimi and Farangis Nazarian, two of Isfahan’s prominent carpet weavers, from 2018 to 2020. The exquisite carpet measures 230 by 170 cm and has a navy-blue background. Its lachaks—the four roughly triangular corner sections surrounding a lachak–toranj-style carpet’s central area—are decorated with golden regular arabesques, “DahanAzhdari” arabesques, “Shah Abbas flowers”, “goljāms”, and other elements, recalling classic Isfahan carpet design styles, Safavid-era motifs, and the art of taz’hib. Rather than a toranj—the round or oval section in the centre of a lachak–toranj carpet—there is a silver six-arm chandelier hanging from the silver arabesque-studded border that separates the central area from the lachaks. The outer border of the carpet is a tilework of shining diamonds, resembling Qajar ayneh-kari (lit. “mirror-work”). In the middle of each side of this border sits a medallion of two concentric ovals that enclose a pair of pink Qajar-style roses, with one of the flowers in each medallion featuring a red outline. The boundary of each inner oval is ornamented on the inside by a series of pearl-like circles, which evokes Sasanian art.

Discussion and analysis

Featuring a traditional design, the lachaks in Carpet of Light (Nour) echo the golden age of Persian carpet, which coincided with the Safavid period. The era was the heyday of the carpet industry in Iran: scores of carpet weaving workshops were active across the country, especially in the then-capital Isfahan and the nearby villages and towns, and splendid carpets were exported to Europe. It was also in this era when the Armenian merchant Sefer Muratowicz was sent by King of Poland Sigismund III Vasa to Iran at the time of Abbas the Great’s reign to strengthen trade relations between the two countries and purchase Persian carpets for Polish royal palaces, which were eventually carpeted with elegant Persian rugs that, according to the carpet scholar Touraj Jouleh, all came from Isfahan. Carpet of Light’s lachaks recall this very era, when Isfahan and Kashan rugs were the finest of their kind in all of the East, according to García de Silva Figueroa, the Spanish ambassador to the court of Abbas the Great.The rich period of Persian art is revived in the lachaks of Carpet of Light (Nour). The further we move from the carpet’s centre, the brighter the design becomes—the lachaks, with their shining arabesques, and the Qajar-inspired border mirror-work are very creatively coloured to appear as if reflecting light. By contrast, moving back towards the centre leads us to a very dark area: the navy blue, plain background.

The designer, Amirhossein Haghighi, intended this juxtaposition to represent the ongoing, gradual decline of traditional Iranian art, which drifted away from its prime—symbolized by the Safavid-inspired golden lachaks—and never again could restore its past glory domestically or internationally. The dark, navy blue background signifies the slow waning of thought and art in the “Iranian world.” But the artist still has hope: Amirhossein Safdarzadeh Haghighi has placed a silver six-armed chandelier where there would traditionally be the toranj, aiming to symbolically keep hope alive for the viewer. He believes that, in the not-too-distant future, culture in the Iranian world will emerge from its current stagnation and weakness and will shine in different domains like it historically has; an idea that he communicates via the chandelier. Although the “light” has in our times gone dim, the means to enlighten oneself and others still exist in the Iranian world, and this is demonstrated by the not-so-shiny and non-golden chandelier. The designer dreams of the day when the Iranian world eventually and slowly emerges from the crisis and revives its active presence on the international scene.

As described earlier about Carpet of Light (Nour), there is a medallion of two concentric ovals in the middle of each side of the mirror-work border. Lined with pearl-like circles on their inner circumference, the medallions are reminiscent of Sasanian art. Pearl-outlined medallions hallmarked Sasanian textiles and occasionally enclosed floral motifs and other decorative elements, inspiring Amirhossein Haghighi to place pink Qajar-style roses inside his pearl-studded medallions.

Delving into the art of the Sasanian, Safavid, and Qajar periods, Amirhossein Haghighi encourages viewers to give hope a chance—especially those viewers who were born into the cultural context of the Iranian world and therefore had to deal with war, chaos, and turmoil for many consecutive years. Negin Alsadat Tabatabaei

Islamic Archaeology PhD graduate from the University of Tehran

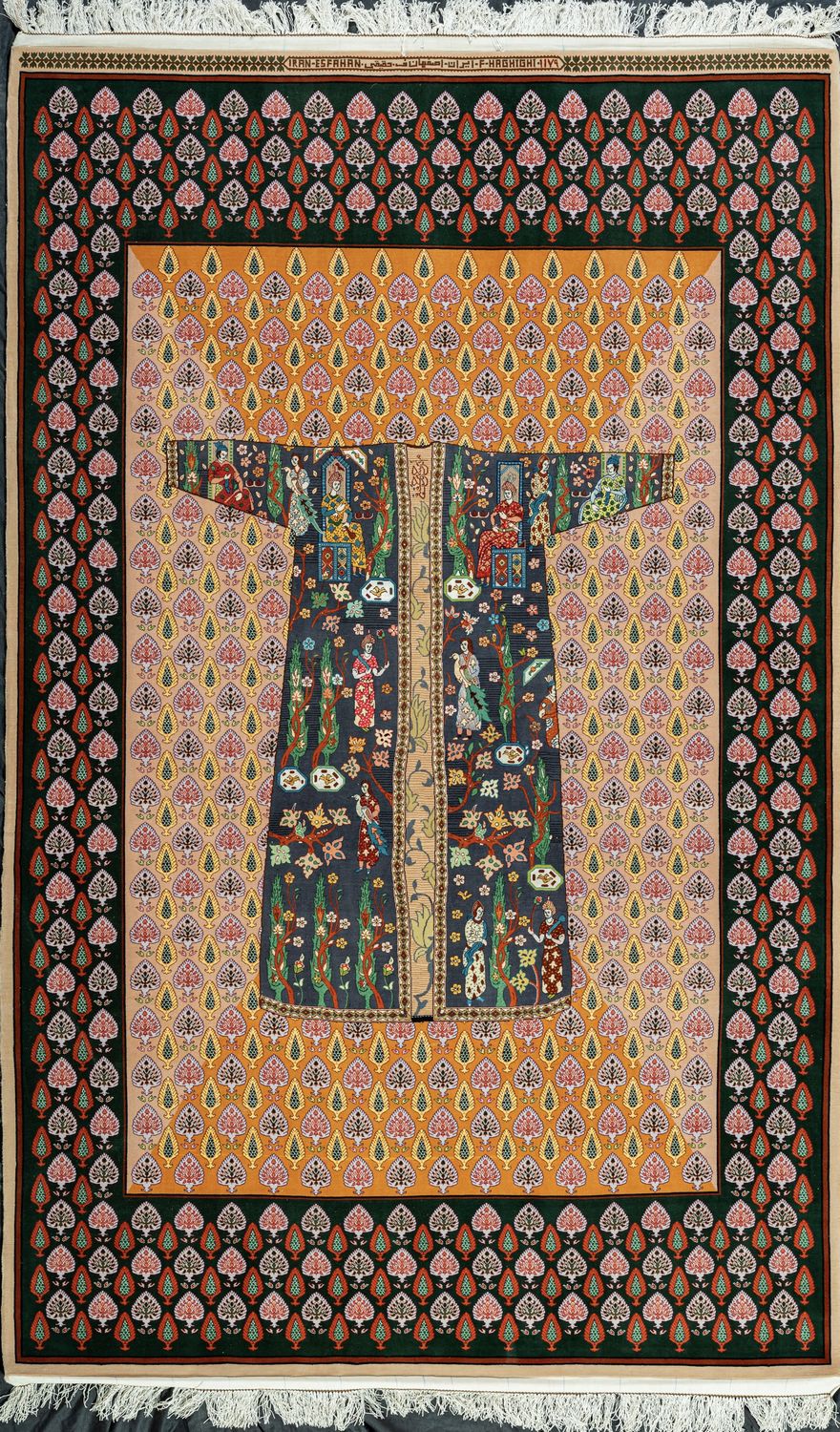

Molk-e Del: A Carpet

Description

Designed in 2018 by Amirhossein Haghighi, the carpet Molk-e Del was woven by Anis Karimi and Farangis Nazarian, two of Isfahan’s prominent carpet weavers, from 2018 to 2020. The exquisite carpet measures 264 by 168 cm and holds in its centre an image of a traditional Persian coat—116 by 113 cm—with a navy-blue base. The coat is decorated with standing and sitting men and women that are inspired in visual style by Timurid and Safavid miniature painting. An idea behind the carpet’s creation was to combine the precious art of Persian apparel-making with a mixture of Timurid and Safavid miniatures into a novel design that was unprecedented in the Iranian carpet tradition. On the left chest of the coat, a king in red sits on a throne that resembles those of the Achaemenid emperors depicted in Persepolis reliefs. Before him stands a blossoming cypress drawn in the manner of Timurid and Safavid painters, with an octagon howz pool positioned just below it. On the left sleeve, the king’s vizier sits behind him on a throne of his own, facing a third man standing before him. Another flowering cypress rises between the vizier and the man, while a similar but partially cropped-out tree is placed behind the vizier. Going down to the middle part of the same half, we see two other blooming trees, one lower than the other and each rising from behind an octagon howz. A woman holding a peacock stands nearby with her back to the higher tree. On the lower part of this side, two men stand facing each other, with yet another in-bloom cypress in between. One of the two men holds a flower in his right hand and a mace in his left. The right side of the coat roughly mirrors the left: a king in yellow sits on an Achaemenid-style throne, with a flowering tree and an octagon howz below it situated in front of him; behind the king, a woman with a peacock in hand stands before a red-wearing vizier sitting on his throne; another flower-bearing tree is placed between the woman and the vizier; in the middle of this side, a pair of blossoming, octagon-howz-bottomed cypresses are planted side by side, and a man stands close by with his back to the trees, holding a flower in one hand and a mace in the other; further down, there is yet another peacock-holding woman, who stands next to a branch with green and golden leaves; finally, three blooming cypresses are lined up in the lowest part of this half. The coat is surrounded by a pattern of small, evenly-spaced cypress motifs that are laid against a pink background on the sides and an orange background on the top and bottom. The border of the carpet is also patterned with similarly-shaped and -arranged but differently-coloured motifs that run over a black background.Discussion and analysis

The designer’s main idea for Molk-e Del was to express his wish for world peace. On both chests of the coat, there is a king on his throne: the carpet’s small world is reigned over by two rulers, yet all things coexist in harmony and peace. On each half, there is a man with a mace in one hand but a flower in the other; a juxtaposition that makes the weapon appear less threatening and directs the viewer’s attention away from it and towards the blossoming trees and tiny flowers that are scattered all over the coat. To portray the utopia he dreams of, the designer looked into traditional Persian painting for inspiration—the illustration on the coat echoes Timurid and Safavid miniatures. Just like in the artworks that inspired it, the scene depicts kings and princes in the company of their servants, surrounded by blooming trees, food, and drink. Some of the Timurid painting influences come from the Herat School: founded in the Timurid period, the School reached its peak during the 38-year reign (1469–1506) of the Timurid ruler Sultan Husayn Bayqara, thanks to the patronage of the art-loving king and Ali-Shir Nava’i, his famous vizier, as well as the mastery of the renowned miniaturist Kamal ud-Din Behzad. Similar to paintings from the Herat School, the positioning of the figures unifies the different areas of the coat’s illustration. Herat School’s brand of naturalism is also present, and flowering cypresses are used liberally—in-bloom trees were common in Persian miniatures from 50 years before Behzad. An interesting quality in Molk-e Del’s coat is that although the elements are designed with some degree of realism, the overall visual style still bears the same level of abstraction that characterized Persian painting. Aided with a correct understanding of his cultural heritage, Amirhossein Haghighi has designed Molk-e Del to remind us that we can live together in peace and amity despite our different views, political positions, religions, and rulers, and be blessed with the fruits of that peaceful coexistence. The designer also wanted to say specifically to the people and rulers of the Middle East that, sadly, they have not seen peace for years. In Molk-e Del, just like in his Carpet of Light(Nour), Amirhossein Haghighi keeps hope alive for the viewers and encourages them to work towards a better tomorrow. Negin Alsadat TabatabaeiIslamic Archaeology PhD graduate from the University of Tehran